Coronavirus lockdown lessons from single-parent scientists

For Prabha Devan, a stem-cell biologist at the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB) in Hyderabad, India, transitioning to remote working during the coronavirus pandemic has been more than just an inconvenience. Not only must she try to finish her research from home but she must also care for and home-school her seven-year-old son. With her family 900 kilometres away in Tamil Nadu in southern India, Devan is completely alone. “I am used to coping on my own, but this seems very bleak,” she says.

CCMB is in the early stages of trying to re-open, but its on-site childcare facilities and schools will stay closed. Devan, who is in the final quarter of her postdoc, fears that if she can’t find help to care for her son, she might have to leave the field to which she has devoted more than a decade of her life.

Many single-parent scientists are struggling to meet the demands of research and family during lockdown. Nature spoke to four of them about their coping strategies.

MELISSA McKENZIE: You can’t do it alone

Melissa McKenzie, developmental neuro-biologist, Columbia University, New York City.

I always feel like I’m playing catch-up. Even in a normal situation, I can’t spend as much time in the laboratory as the next person. Now, I have to be much more organized and I have to put a lot more focus on everything that I do. I feel like I have to constantly work out how I can be effective, that I’m doing over and above what I normally have to do, and that I’m never going to get on top of everything.

I did my MD–PhD at New York University School of Medicine, where I studied developmental neurobiology, and now I’m a postdoc at Columbia. I had my daughter six years ago during my PhD. I’m not a full-time single parent — my ex-husband and I share custody. At the moment, however, we don’t have our usual custody arrangement. Because my job is a bit more flexible, I have her most weekdays so that he can attend his virtual business meetings without interruption.

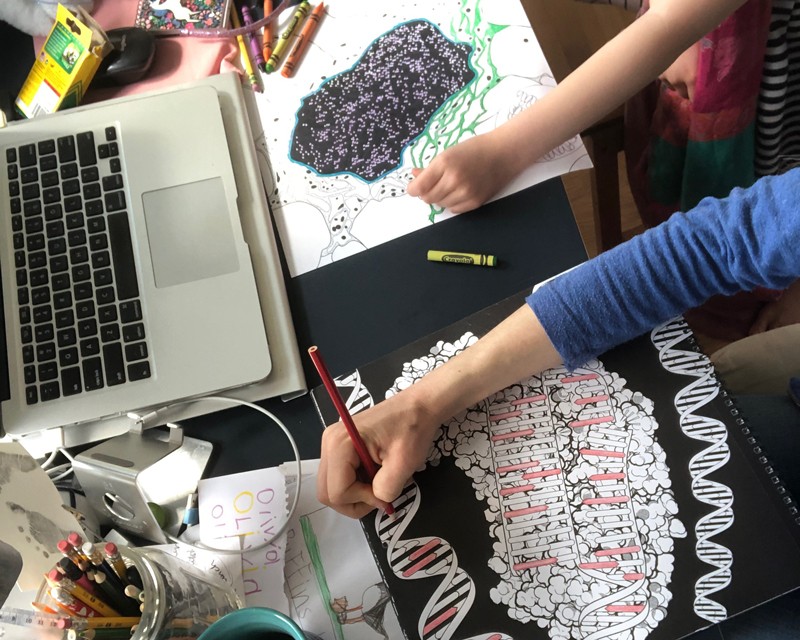

Home-schooling is really challenging. Although my daughter is only in kindergarten, she and her classmates have had a very rigorous course load. And the work they are given requires participation from parents. When she’s here, I can’t rely on getting any work done. The things that I can do from home are not actual experiments. I’m reviewing papers and helping to prepare manuscripts. For those jobs, you need quiet and extended periods of time to focus, with little switching between tasks. But when my daughter is around, those windows of time are very unpredictable. So if she becomes really engaged in something, I have to be ready to do whatever I’m going to do. If I’m not, I’m going to lose that hour. It makes it very challenging.

During my PhD, my principal investigator (PI) gave me as much time as I needed after I gave birth, and my current PI has also been very supportive. He has three young children, so everyone in the lab is very understanding during Zoom meetings when there are kids running around in the background. We’re also very aware of scheduling — e-mails will be replied to after our children’s bedtimes. From the beginning, my daughter has come to all the lab holiday parties and get-togethers. If I come in to work at the weekend, sometimes I bring her and she stays in the conference room.

I’ve been pleased with how my school district has been approaching the situation from a health standpoint, but for childcare, it hasn’t been ideal. There are so many moving parts, and so many possible exposures to the coronavirus. The uncertainty is crazy. It’s going to be more expensive, but I’ve signed my daughter up to do supervised distance learning with a daycare provider in the autumn instead of going back to school — I feel like the risk of infection is lower than at school. The school is lending the children Chromebooks and she’ll attend her first-grade class virtually from daycare with a small group of kids.

Still, you can’t expect to do it all by yourself. The other day, I needed to get something done, and a bunch of kids I know were outside riding their bikes, but staying pretty far away from each other. So I asked their parents if the group could keep an eye on my daughter while she rode with them for a while. I got that task done. And that was great.

ELENA TOBOLKINA: Prioritize your tasks

Elena Tobolkina, pharmaceutical chemist, University of Geneva, Switzerland.

You have to be responsible at work — and at home. I need to find activities for my oldest child, who is five, and childcare for my younger one, who is just a few months old. At the same time, I am still trying keep up with lab work, because I have to be back on campus this month — the semester starts in September.

It’s very difficult, because I feel so much pressure — I have to take care of everyone and myself. And I worry about getting too stressed because I’m still breastfeeding and I might lose my milk supply.

I’m originally from Russia, where I graduated from St Petersburg State University in physical chemistry. I ended up at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), where I got my PhD in analytical chemistry. At the end of my PhD, I became pregnant with my first child.

I was invited to do a postdoc at the University of Oxford, UK, in biochemistry and organic chemistry. I didn’t want my supervisor to know that I had a child because I was worried that some scientists might not want to work with women who have children. So I left my daughter with my parents in St Petersburg, because finding an affordable nursery was impossible in Oxford. After one year, I ended my contract so that I could be reunited with my daughter, and we moved back to Switzerland. As my career began to stabilize, I got back together with my former partner and my younger child was born in April. My partner is overseas much of the time and can’t help with the childcare.

During the lockdown, I have found it is best to stay calm, even though this is super hard at times. Your children should always see you as strong and decisive regardless of whether you feel that way. I also realized I needed to prioritize tasks at home, the way I did at work: I concentrate on one thing at a time. My oldest daughter wakes up at 7 a.m., and knows what she must do — take a shower, get dressed, do some Russian and French classes, and play by herself.

I also give her some household tasks so she can be involved in the routine. And I focus on the positives — it’s been a great opportunity to spend time with my family, and learn how to better communicate with them.

DAVID SMITH: Success might look different

David Smith, chemist, University of York, UK.

A lot of my team’s research is inspired by the health problems experienced by my late husband, Sam, who had cystic fibrosis and, in 2011, a double lung transplant. Sam passed away in February 2019 as a result of lung-transplant rejection. Our son is now 7 years old and I am a single parent.

Since lockdown, things have been incredibly hard, particularly because of school closures. Before the pandemic, my son was in school for 30 hours a week, and then had another 7 hours of care in breakfast club, after-school club and with his grandma. Suddenly all those hours of support disappeared. I still had online classes to teach, exams to prepare and mark, project dissertations to read, external examinations to give, researchers to supervise, student support to deliver and committee meetings to attend on Zoom. I had no childcare at all and had to home-school my son and do my job. And it all essentially happened overnight.

Educationally, my son struggles, and he is already about a year behind his peers. This also made me feel intense pressure to do my best to give him the one-to-one educational support he needs. But it can be very challenging and tiring to teach him.

It remains to be seen how much damage being unable to work will do to my research career. I am conscious that other academics are finding this the best time ever for thinking about science and writing new grants. I am so exhausted, I’m barely able to pull my thoughts together to make a cup of tea at times.

I would like other academics to realize that everyone’s experience of lockdown is different. I don’t wish to belittle what anyone has gone through at this time. Some have struggled with loneliness or separation. For some, mental-health problems have flared up. Others have struggled in households where they do not feel properly safe.

It is essential that we listen to everybody’s experiences and take them into account as we move forward. In particular, it is important for senior academics to understand that ‘success’ might look somewhat different for some researchers and academics as a result of the crisis. For some, amazing success might be publishing one small paper, managing to deliver a class — or just holding it together.

PRABHA DEVAN: No choice but to resign

Prabha Devan, stem-cell biologist, Centre For Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad, India.

Before the pandemic, I would wake up at 4 a.m., start some household chores, finish cooking and get my 7-year-old son ready for school. Once he left, I would play tennis or go to the gym for an hour, and then, by 9 or 9:30 a.m., arrive at the lab. I would work there until 3:30 or 4 p.m., when my son came home, spend some time with him and then go back to the lab for another two hours. Sometimes I’d be there until 8 p.m. in the evening.

With the shutdown in late March, the government said that only essential lab personnel could go in, and, soon after, this was reduced to even fewer staff. But even if I were allowed to go in, I couldn’t because of my son. None of the childcare centres are open, so I have to be at home taking care of him. There’s no option for university or private childcare. I asked my PI for advice, and she said to finish writing my manuscript by June from home, but that I’d have to come back in by July and finish all my experiments because my postdoc contract expires in September. Returning to the lab is almost impossible, but I’m trying to finish what I can.

Scientists need to be more open about the childcare crisis during the pandemic. The lack of childcare is squeezing women out of science. Some of my colleagues seem to treat the problem as if it’s my choice to be here and to bring my child into the lab. It is, but I’m doing it because I don’t have any institutional childcare support. I am telling my story to help create a unified voice for our basic right to childcare in the workplace, and to encourage other scientists to ask their parent colleagues how they can help. I felt too guilty to ask for support.

I know every household has its own difficulties, but I live alone with no family support. I don’t even have any close friends nearby to help out. And I just wonder whether I’m really the odd one out or whether there are lots of other women in crisis.