The Rearview Mirror: The First Auto Race in America

It is said that the first automobile race occurred when the second automobile was built.

But the first official automobile race occurred this week in 1895 in Chicago, Illinois after H.H. Kohlsaat, owner of the Chicago Times Herald, read about the world’s first automobile race in France.

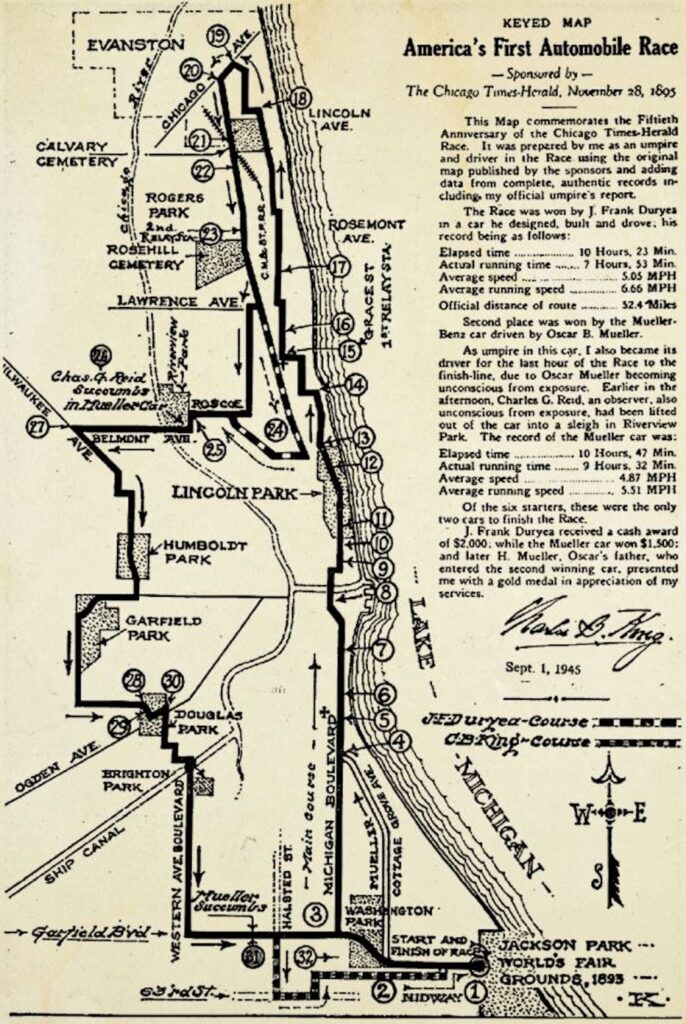

In an effort to boost circulation and woo advertisers, he decided to sponsor a race from downtown Chicago to Milwaukee, and back for “inventors who can construct practicable, self-propelling road carriages.” But poor roads north of Racine prompted organizers to shorten the route, running 54 miles from Chicago to Evanston, Illinois and back.

The contest was open to all foreign or domestic cars, whether powered by gas, electricity, or steam. First prize is $2,000 and a gold medal. Second prize was nearly as generous, at $1,500, while third prize was $1,000. That’s the equivalent of $59,602, $44,701 and $29,801 respectively when adjusted for inflation.

Initially meant to be run Nov. 9, Kohlsaat postpones the contest.

“The reason for the postponement was chiefly the shortness of the time for preparation,” Kohlsaat said. “A number of foreign machines were shipped on a steamer, which is overdue. Then, the home manufacturers found the time short.” In addition, “the judges said they were convinced that a great number of manufacturers were honestly desirous of competing for the prize, and would do so if the race should be postponed.”

And so, the race is postponed until Thanksgiving, although the new date held out the possibility of becoming an annual Thanksgiving tradition. Or at least so Kohlsaat hoped.

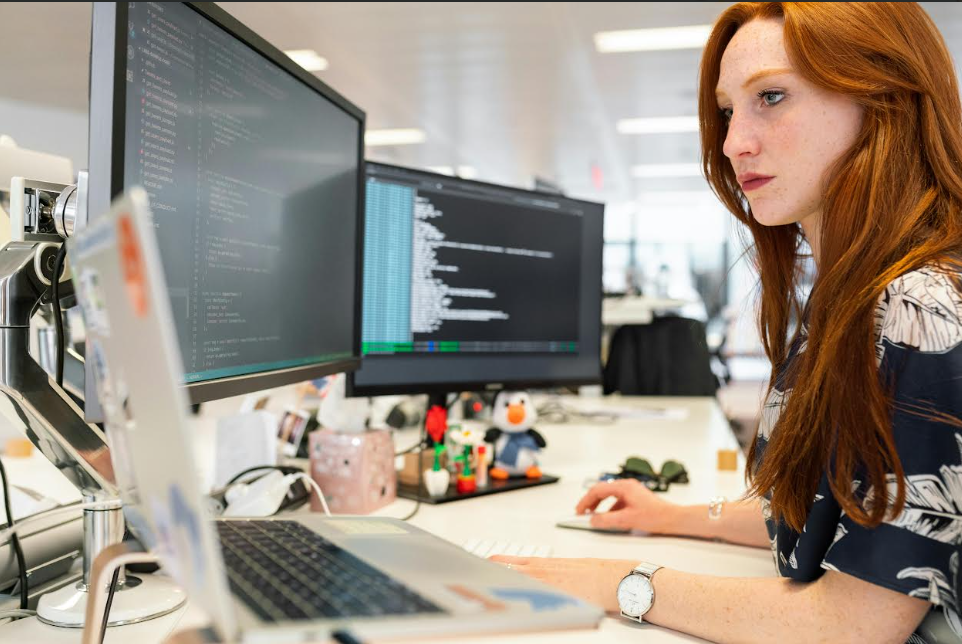

The auto industry in 1895

The auto industry in 1895 could best be described in two words: what industry? The car had only been introduced to America in 1893. In fact, the device was so new, Chicago newspapers didn’t know what to call them.

“There was considerable opposition to calling the horseless carriage ‘automobile,’ as the name was too Frenchy,” Kohlsaat said in 1931 in the Saturday Evening Post. “So the Times Herald offered $500 for a name, and ‘motocycle’ was awarded the prize.”

As Thanksgiving Day approached, the weather seemed unusually fine for a race — until the night before. Then, a snowstorm moved in, dumping 6 inches of fresh snow followed by heavy winds that create drifts of up to 24 inches — far from ideal race conditions.

Nevertheless, with the mercury hovering at 30 degrees, six cars approach the starting line at Jackson Park, which runs along Lake Michigan on the south side of Chicago.

Competitors line up

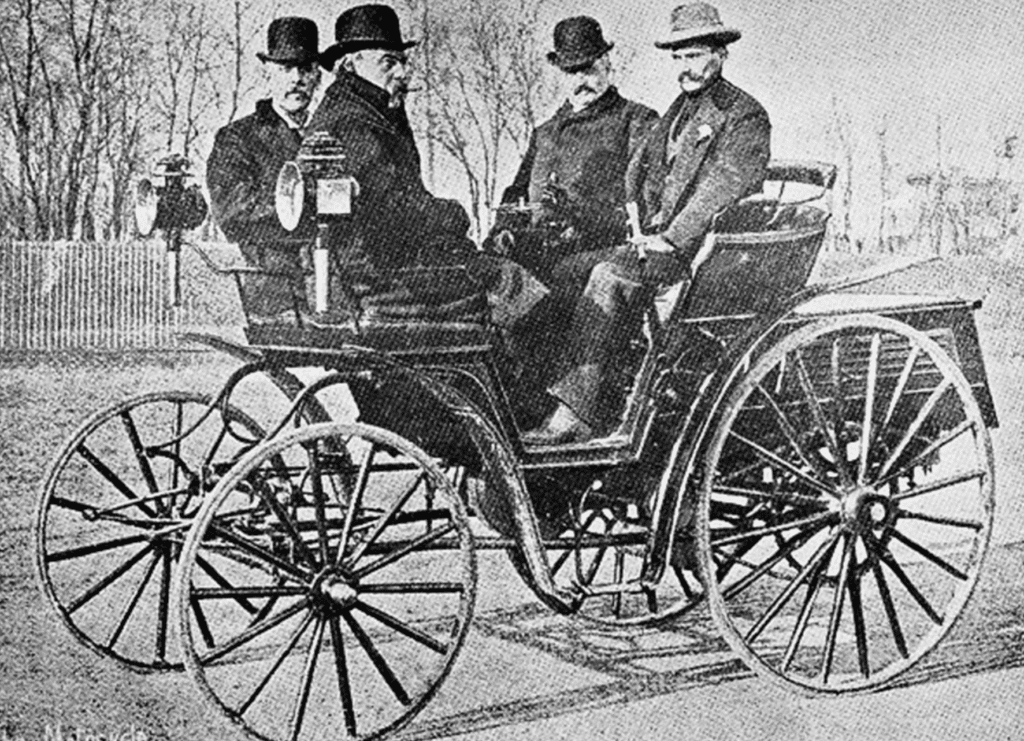

Not surprisingly, three of the six cars were German-built Benzes, and why not? Karl Benz had invented the modern gas-powered car, powered by a 1.0-liter, 1.5-horsepower engine and a single speed transmission.

One Benz is sponsored by Macy’s Department Store of New York, another representing the De La Verne Refrigerator Machine Co. — also of New York, and the third by Oscar Mueller of Decatur, Illinois. The other gas-powered entry was a Duryea built by brothers Charles and Frank Duryea of Springfield, Massachusetts. Its 1-cylinder engine generated 4 horsepower through a friction transmission, commonly used today in scooters.

Two electrics also competed. The first is a 4-hp Sturges Electric, America’s first successful four-wheel electric car, built in Des Moines, Iowa by Morrison Electric. The other is a Morris and Salom Electrobat, built in Philadelphia and powered by two 1.5-hp motors mounted on the front axle. A Haynes & Apperson started out from the company’s headquarters on Wabash Avenue, but dropped out as it couldn’t make it to the starting line, according The Chicago Chronicle newspaper.

All cars had a driver and a referee riding shotgun.

Ready, steady, go

At 8:55 a.m., the race begins led by the Duryea, and followed by Macy’s Benz, the Salom and Morris Electrobat, the De La Vergne Benz, Mueller’s Benz, and the Sturges Electric. But it is far from a smooth start. Most cars use pneumatic tires, which perform poorly when tackling snow. “Much hand power was used in getting the machines under headway,” The Chicago Chronicle reports.

The Duryea maintains its lead through most of the race, followed closely by Macy’s Benz. The Duryea did slip from the lead when it lost one of its rubber tires. The team stopped to tie the tube back onto the wheel, returned to the race, and passed Macy’s Benz to once more take the lead, a spot it maintained to the race’s end.

But all was not smooth sailing.

America in 1895 lacked standardized federal roads and street signs, so getting lost was easy, which the Duryea did, causing the vehicle to lose time. Of course, getting lost wasn’t the only risk; these machines weren’t reliable, and problems frequently cropped up. The Duryea’s steering arm snapped and had to be repaired by a blacksmith.

Macy’s Benz saw its steering gear fail, and was overtaken halfway through the race by Mueller’s Benz. It also ran into an overturned sleigh late in the race before later crashing into the rear of a streetcar, causing it to drop out of the race. The Electrobat ran so far ahead of its supply wagon, it ran out of juice and it too dropped out of the race at Lincoln Park.

The cars also frightened horses, causing buggies to crash. “Michigan Boulevard was a procession of prancing, snorting horses that shied at every machine as it passed,” wrote one reporter. “That there were no runaways is marvelous.”

It was slow going, as drivers fought not just terrible road conditions, but freezing winds, as none of the cars were enclosed. As afternoon turned to evening, all of the cars had dropped out except for Duryea and Mueller’s Benz. Skies were darkening, and the fatigue of driving for nine hours was taking its toll. Mueller was fighting to maintain consciousness.

At 7:18 p.m., the Duryea, driven by Frank Duryea, crosses the finish line. It had taken him 10 hours and 23 minutes to drive 52.4 mile. He had averaged 7 mph and used 3.5 gallons of gas for an average of 15 mpg. Two hours later, Mueller’s Benz crosses the finish line, winning second place. But Mueller isn’t driving; the referee is. The cold caused Mueller to pass out.

And with that, the first auto race is over, although there were no officials there to witness it.

“The judges had become disgusted and quit,” wrote the Chicago Tribune. “No one witnessed the finish but two reporters.”

What happens next

The next morning, the judges met to decide how to distribute the prize money. Duryea gets $2,000, Mueller receives $1,500. Macy’s and Sturges each receive $500, while Morris and Salom are awarded a gold medal, Haynes & Apperson get $150, and De La Vergne receives $50. All contestants violated rules of the race, however.

But Kohlsaat is pleased.

“With good roads, every machine would have gone over the course,” Kohlsaat said the day after the race. “A better test of the utility of road machines could not have been made, and I feel assured that the beginning has been made in a new method of transportation.”

He would be right.

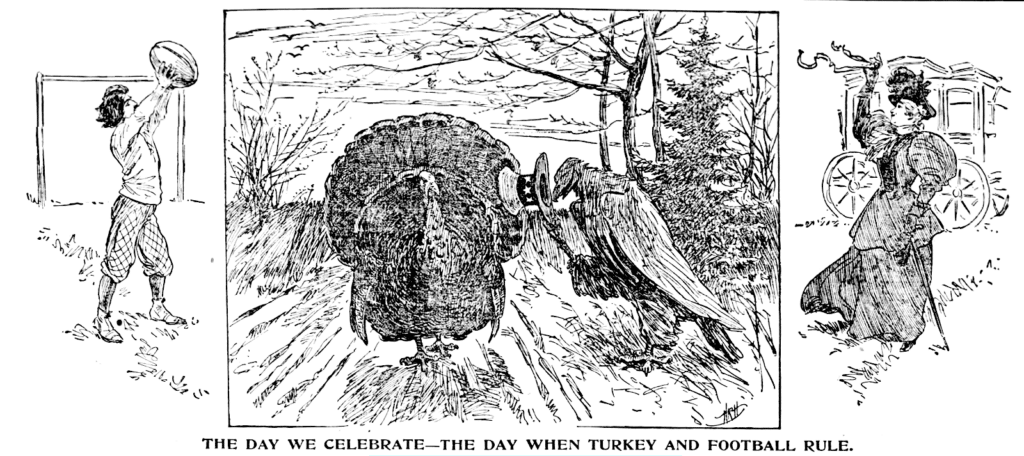

But his attempt at establishing the race as an annual Thanksgiving tradition fail. That honor goes to another sport, as the Chicago Tribune so aptly reported that same year. Thanksgiving, it wrote in a front-page cartoon, is “the day when football and turkey rule.”