Black businesses aim to help save the planet

As a child growing up in Richmond, California, the future held one of two possibilities in Darrell Jobe’s young mind: play for the NFL or become a microbiologist. But at 13, everything changed when he became homeless, dropped out of school and joined a gang.

That he celebrates Earth Day on Friday as the owner of Vericool, which produces environmentally safe packaging products, speaks to his unpredictable journey. He says it also speaks to his never-wavering interest in protecting the earth, even after he’s served short stints in prison.

“I love animals and if you do, you care about the environment because that’s how they live,” Jobe, 42, said. “All the stuff that went on in my life, that respect for the earth never left me. To get beyond all that and to be able to do something to protect the environment is rewarding.”

He invented the world’s first recyclable or biodegradable ice chest cooler in 2017 and developed a compostable and recyclable thermal solution for shipping Covid-19 vaccines in place of environmentally unfriendly Styrofoam coolers.

“My thing was, if I could create solutions — products that were safe for the environment — eventually there will be bans on products that are not safe for the environment,” Jobe said. “I thought: How do I create a cooler that would eliminate harmful Styrofoam coolers? How do I create a product that eliminates plastic gel packs? The same with bulk manufacturing and petroleum-based packing. That mentality — being about protecting the earth — inspires me.”

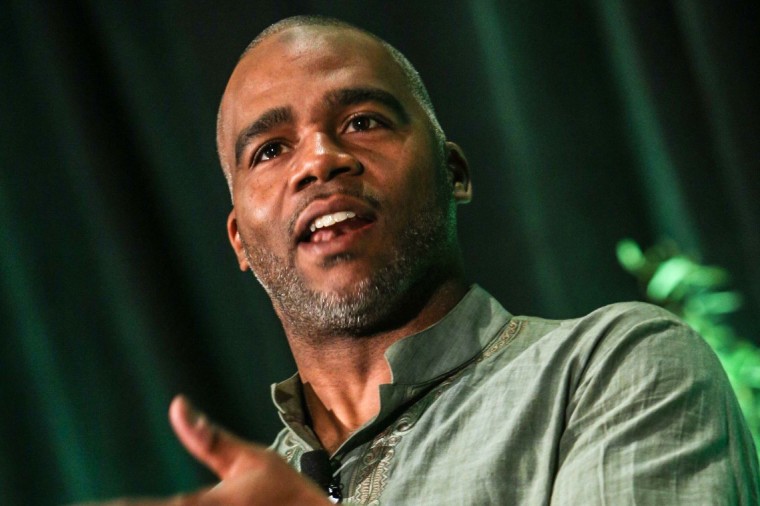

Jobe is among many Black entrepreneurs who have created businesses that focus on products that preserve the earth. More than a billion people around the world celebrate Earth Day Friday, an annual opportunity to demonstrate support for environmental protection, and the emerging business owners are especially noted, longtime environmentalist Ibrahim Abdul-Matin said.

“They represent a movement of human beings that are concerned about how we live the best possible way on the planet Earth — and how we solve problems better than we’ve ever done before,” said Abdul-Matin, author of “Green Deen: What Islam Teaches About Protecting the Planet.”

The stereotype of an environmental advocate had long been white and wealthy. But Abdul-Matin sees a shift, and identifies the modern environmental justice movement in America as originating in 1982 in North Carolina, where a predominantly Black community in Warren County protested the discarding of toxic soil into a nearby landfill. Since then, Black organizations and individuals have emerged more and more to address the environment, understanding their roles are critical to the safety of themselves and the planet.

“Our struggles are all connected because we’re all on the planet Earth together,” Abdul-Matin said. “And we should care because it’s absolutely essential. We’re human beings. The only home we’re going to have is the land beneath our feet. So, it’s encouraging to see Black people continuing to join the cause.”

While Jobe maintained an appreciation for the environment, it was not until he was 25, out of prison and working for a plastics company that he altered his reality. He said he eventually was introduced to a retiree named Gary Lantz, who schooled him on thermodynamics, the study of the relations between heat, work, temperature and energy.

He was fascinated by the work, “but I noticed that all the companies were choosing all detrimental, petroleum-based plastics, Styrofoam, single-use plastics,” he said. “All of the stuff that was just garbage, detrimental to the environment.”

Jobe expanded what he learned to create Vericool, based in Livermore, California, to help revolutionize the packaging business. His rise is unique in that he had no formal education beyond the eighth grade. He also spent close to three years in prison for auto theft and possession of a stolen handgun. Those transgressions did not diminish his creative instincts.

He considers himself a self-taught inventor of technologies for which he holds 17 U.S. and five international patents. About 25 percent of his Vericool staff are formerly incarcerated people. “We have to reduce the recidivism rate,” he said. “They deserve a second chance. If anyone knows the value of that, it’s me.”

In 2021, Tanjuria Willis, a former electrical engineer at a nuclear facility, expanded her consignment shop, eKlozet, by creating the Atlanta Sustainable Fashion Week.

The event featured models strutting in garments and accessories that are “produced in a socially responsible manner or promotes a circular economy, thereby extending the life cycle of the garment and keeping them out of the landfill,” she said. “Sustainable textiles are created with the environment in mind. The aim is to reduce harm through the production process, fiber properties and environmental impact contributing to the reduction of waste, water conservation, lowered carbon emissions and soil regeneration.”

Environmentally sustainable fabrics include textiles such as organic cotton, recycled cotton, organic hemp, organic linen, organic bamboo and cork, Willis s

aid.

Her event also includes two panel discussions with the topics: “How My Fast Fashion Choices Affect The World” and “Are My Clothes Killing Me?”

“I’ve always cared about the environment,” Willis said, “but it crystalized for me when fast fashion became so popular. I came to understand how large this industry’s contribution is to landfills.”

She said about 80 percent of the energy used in the fashion industry is used in textile manufacturing.

“From the perspective of consumers, it is hard to understand the direct correlation between fashion and textile pollution and its impact on their life,” Willis said. “However, when we look at the unpredictable weather changes, the increase in natural disasters as well as increased health concerns, research shows that textile pollution is part of the problem. I wanted to leverage fashion to bring this issue to the forefront, develop awareness with an out-of-the-box concept.”

That concept has been well-received. Atlanta Sustainable Fashion Week begins Saturday, with tickets hard to come by.

“Everyone should be aware of what they wear,” Willis said. “Just like we read the labels of food, we should read the labels of our clothing. It takes about 1,800 gallons of water to grow enough cotton for one pair of jeans and about 400 gallons to create one T-shirt. Fashion production makes up about 10 percent of our carbon emissions, dries up water sources, and pollutes rivers and streams. Textile pollution is the No. 2 pollutant to the landfills, with about 85 percent going to the dump each year.”

The more the environmentally conscious share about the importance of protecting the earth, the more Black people will understand how much it impacts them and their lives and health, Abdul-Matin said.

“I would venture to say that most Black folks have a deep tradition that is already connected to the land and connected to the earth,” he added. “And if they don’t, they may have some relatives or some folks in their families that are. We should care. We should care because it’s absolutely essential. You can’t assume the certain things that happen are part of the natural world or are random occurrences. Human impact is obvious.”

And, Willis said, there is another key factor to being an Earth Day supporter. “The fashion industry is built on the oppression of Black and brown people,” she said. “We continue to endure toxic manufacturing and lack of fair pay, all to provide that fast fashion ‘$10’ dress. The contaminated waters from dyes and the landfills are typically close to Black and brown communities.

“The consumer spending power in the Black community is staggering. If we purchased just 10 percent of our clothing from a sustainable designer, we could effect change on our carbon footprint. We have the power. The question is: Do we have the will?”